The COVID-19 pandemic continues to have huge impacts on public schools in South Carolina and across the nation affecting both student achievement and student well-being. Most prominent are these three:

- Large increases in chronic absenteeism resulting in lower achievement levels for these students and for all students in classes with high levels of absenteeism;

- An increase in children and youth battling mental health issues, and a steep decline in the social-emotional skills and behaviors of students;

- A major drop in math achievement, which remains below pre-pandemic levels.

Large Increases in Chronic Absenteeism

Nationally and across South Carolina, a dramatic surge in student chronic absenteeism has occurred in the years coming out of the pandemic. Students who are chronically absent suffer academically and are more likely to drop out. The achievement of students who consistently attend but are in classes with high levels of absenteeism is also harmed.

Chronically absent students are those missing 10 percent or more school days in a school year (18 days for South Carolina schools) for any reason, excused or unexcused.

In the U.S., nearly 14.7 million students (30%) were chronically absent in 2021-22—almost doubling the more than 8 million pre-COVID-19 chronic absences.1 And more students attended a school with a high level of chronic absenteeism. In 2021-22, two-thirds (66%) of students “attended a school with high or extreme levels of chronic absence.” Before the Covid-19 pandemic, this only applied to a quarter (25%) of all students.2

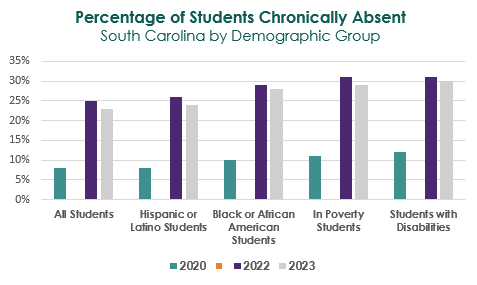

In South Carolina public schools in the 2022-23 school year, nearly one-fourth of students (23%) were chronically absent. Many subgroups had higher rates (see examples in the chart on the right). In all cases the percentage dropped from the previous year but was still two-and-a-half to three times higher than it was pre-pandemic. View more facts–go to “See More: Chronic Absenteeism” in the “Students” data section of this website).

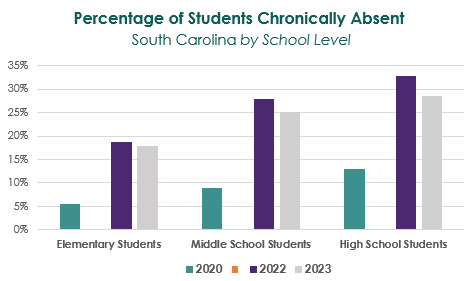

Nationally and in the state, large increases in chronic absenteeism occurred post-pandemic at all school levels–elementary, middle and high school–with slight drops in the latest year. Still, rates for 2022-23 (ranging from 18% to 28%) are two to three times higher than before the pandemic (see chart below).

School districts and schools in the state with much higher rates include eleven school districts with chronic absenteeism rates above 30% and twelve schools with rates above 50%. (Discover similar facts using the ”Comparisons” table in the “Students” data section of this website.)

Chronic absenteeism has become a huge challenge for public schools in the years coming out of the COVID-19 pandemic. “Chronic absenteeism often signals that students are experiencing untreated health needs, transportation problems, mental health issues, or other significant challenges”3 (see next section below). The rapid increase in the level of chronic absence can easily overwhelm a school’s capacity to respond.4

Student performance suffers. As early as kindergarten, achievement in reading and mathematics is hindered for students who are chronically absent. Poor attendance, such as in 6th and 9th grade, is a strong predictor of dropping out of school. Chronic absence even in elementary school is linked to an increased likelihood of dropping out and holds true even if attendance improves over time.

Chronic absenteeism has also been found to have negative impacts on the achievement of classmates.5 Students who do regularly attend classes suffer in both reading and math when large numbers of their peers fail to show up.6

Harm to Mental Health and Social-Emotional Skills

The COVID-19 pandemic worsened a growing crisis in student mental health—an upward trend in depression, anxiety and suicide already underway before the pandemic.7 Between 2009 and 2019, the percentage of teens, nationally, who reported having “persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness” rose from 26 percent to 37 percent. In 2021, the figure rose to 44 percent.8 Rates of childhood suicide rose steadily between 2010 and 2020 and by 2018 suicide was the second leading cause of death for youth ages 10-24.9 In 2021, one in five said they had contemplated suicide.

In October of that year, the American Academy of Pediatrics declared “a national emergency in child and adolescent mental health” that will have lasting impacts on students, their families, and their communities.10

During school shutdowns and remote learning, young people were apart from friends and social connections and had much less structure and routine. Many families were under added financial stress—29% of students reported a parent or other adult in their home lost a job–and many young people endured the trauma of losing loved ones to COVID-19.11

As a result, schools are now seeing a large number of students acting younger than their age and many exhibiting more behavioral issues and aggression. “During the months they were learning remotely, students didn’t have the opportunities for developing the social skills that normally happen during their period of development.”12

Nationally, special needs students and those with an existing mental health diagnosis, lost significant in-person support at school and fell far behind their peers both academically and developmentally. Other children experienced a delay in having these conditions identified as they were away from school staff who might have spotted symptoms early on. By the time they returned to school and received support, they were doing worse.13

Other specific groups of students have been highly affected. “LGBTQ students have been particularly vulnerable reporting higher rates of suicide attempts and poor mental health. Nearly half of gay, lesbian, and bisexual teens said they had contemplated suicide during the pandemic, compared with 14 percent of their heterosexual peers. Girls reported faring worse than boys. They were twice as likely to report poor mental health. More than 1 in 4 girls reported that they had seriously contemplated attempting suicide during the pandemic, twice the rate of boys.”14

School connectedness had an important effect on students during this time. “Youth who felt connected to adults and peers at school were significantly less likely than those who did not, to report persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness (35% vs. 53%); that they seriously considered attempting suicide (14% vs. 26%); or attempted suicide (6% vs. 12%).”15

The higher incidence of students with deteriorated mental health and/or under-age social-emotional skills will persist among pandemic students. Teachers face the additional challenge of understanding, identifying and responding to these issues for a large number of students.16

Go to “Learn More” to read about the impact of the pandemic on the mental and emotional health of teachers in “Work Conditions.”

Decline in Math Achievement

Middle-school math achievement suffered greatly coming out of the COVID-19 pandemic both nationally and in South Carolina and remains lower than before the pandemic.

Nationally, the average math score for 13-year-old students was 9 points lower in 2023 than in 2020 and 14 points lower than in 2012 (NAEP* Long-Term Trend assessment). The drop was the “single largest decline” in the last 50 years. “The math score for the lowest-performing students returned to levels last seen in the 1970s.”

While national score declines cut across student subgroups, achievement gaps for lower performing students and those of color grew larger. Math scores declined between 2020 and 2023 for both low-achieving and high-achieving students but declines were greater for lower-performing students. Declines occurred for all major demographic groups, but the declines were less for White students (6 points) than Black (13 points) and Hispanic (10 points) students.17

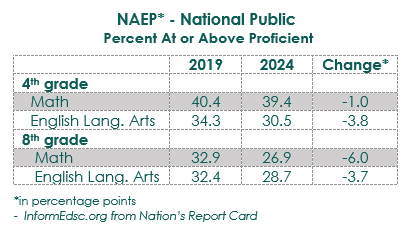

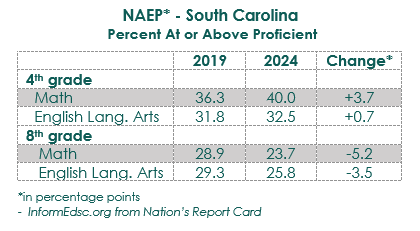

Nationally, a post-pandemic decline in math achievement for this age group also shows up in biennial NAEP assessments (but moved back one year because of the pandemic). As shown in the “NAEP – National Public” table, 8th-grade math achievement has suffered by 6 percentage points. For South Carolina achievement declined by 5 percentage points. However, in both cases, the change in 4th-grade math achievement was better than for English Language Arts with achievement levels nearly at or higher than they were before the pandemic. (For more on NAEP results, see the “Achievement” data section of this website.)

Math proficiency in eighth-grade is a strong predictor of high school, college and career success.18 Poor performance limits a student’s access to advanced math and science courses such as calculus and physics.19 And the overall level of academic achievement students attain by eighth grade has a larger impact than high school academic achievement on their college and career readiness.20

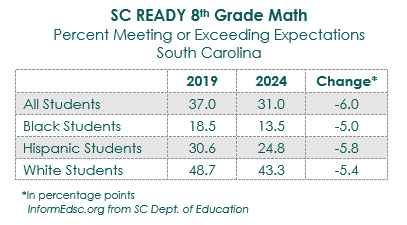

In South Carolina, significant post-pandemic drops have also occurred in 8th-grade math achievement on the SC READY state assessment. Unlike the national math results discussed above, scores declined similarly across major racial/ethnicity groups in the state from the last pre-pandemic assessment in 2019 to 2024 (see the table below). Look in the “Achievement” data section of this website for more SC READY results.)

What to do? When it comes to student performance on reading and math tests, teachers are estimated to have two to three times the effect of any other school factor,21 and the effect of good teachers is greatest upon the most disadvantaged children.22

According to a Stanford University report, “The biggest problem of education during the pandemic has been depriving students of the full abilities of their most effective teachers. Recovery from the damage of these years can only come from an expanded role for these teachers.”23

More facts on this topic can be found on this website. Search on “absenteeism,” “achievement,” “math,” or other terms from this post to see where more information is available.

*NAEP – National Assessment of Educational Progress (The Nation’s Report Card).

Notes

1Attendance Works, “Chronic Absence: The Problem.”

2Chang, H., Balfanz, R. and Byrnes, V., “Rising Tide of Chronic Absence Challenges Schools,” Attendance Works and Johns Hopkins University, 2023.

3 “Tracking State Trends in Chronic Absenteeism,” FutureEd, 2023.

4Chang.

5Center for Research in Education and Social Policy, “Chronic Absenteeism and its Impact on Achievement,” University of Delaware, 2018.

6Gottfried, M. A., ”Chronic Absenteeism in the Classroom Context: Effects on Achievement,” Urban Education, 2019.

7Miller, C. C. and Pallaro, B., “362 School Counselors on the Pandemic’s Effect on Children: ‘Anxiety Is Filling Our Kids’ In a Times survey, counselors said students are behind in their abilities to learn, cope and relate.,” New York Times, 2022.

8Balingit, M., “’A cry for help’: CDC warns of a steep decline in teen mental health,” Washington Post, 2022.

9Declaration of a National Emergency in Child and Adolescent Mental Health from the American Academy of Pediatrics, American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Children’s Hospital Association, 2021.

10Balingit.

11Stone, M., “Why America Has a Youth Mental Health Crisis, and How Schools Can Help,” EdWeek, 2023; and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “New CDC data illuminate youth mental health threats during the COVID-19 pandemic,” U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, 2022.

12 Miller and Pallaro; and Chatterjee, R. “Kids are back in school — and struggling with mental health issues,” NPR, 2022.

13Chatterjee.

14Balingit.

15Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

16Will, M., “The Teaching Profession in 2021 (in Charts).” EdWeek, 2021.

17National Center for Education Statistics, “No ‘Green Shoots’ of Academic Recovery as 2022–23 Mathematics, Reading Scores of 13-Year-Olds Decline,” U.S. Dept. of Education, 2023.

18Indiana Youth Institute, “The Importance of 3rd Grade Reading and 8th Grade Math,” 2021.

19The Opportunity Trust, “8th Grade Math Proficiency.”

20StriveTogether, “Cradle-to-career outcomes: Impacts on economic mobility and equity,” 2022.

21Opper, I. M. “Teachers Matter: Understanding Teachers’ Impact on Student Achievement.” RAND Corporation, 2019.

22Goldhaber, Dan. “In Schools, Teacher Quality Matters Most.” Education Next, Vol. 16, No. 2., Spring 2016.

23Hanushek, E., “A simple and complete solution to the learning loss problem,” Institute for Economic Policy Research, Stanford University, 2022)

20241231