May 2025

Executive Summary

School districts in South Carolina are losing a large and growing amount of local revenue for school operations from the total property tax exemption for primary residence homes and corporate tax abatements. These come from laws established by the state legislature and imposed on school districts which have no say in the matter.

School districts have been losing local tax revenue due to state “property tax relief” laws such as Act 388 (See Appendix). This “relief” fully exempts homeowners from paying the school operations property tax on their primary residence. The state only partially reimburses districts for this revenue loss. Based on the current trend, the net operations revenue loss for all school districts in South Carolina is now above $1 billion per year and growing.

Many districts have also been losing property tax revenue due to fee-in-lieu of taxes (FILOT) and other economic development corporate tax abatement incentives–incentives established by the state that counties can give for large corporate and industrial investments (See Appendix). Again, there is only partial reimbursement for that loss. The net operations revenue loss across all school districts in South Carolina is around $400 million per year.

Combined, the average school district loses tens of millions of dollars in local revenue for operations every year due to the state-established abatements and full tax exemption. In combination, the net operations revenue loss for all school districts in South Carolina is nearing $1.5 billion per year ($2,000 per pupil) and growing.

Sections:

- Quick Overview: School Property Taxes

- Lost Revenue: Property Tax Exemption for Primary Residence Homes

- Lost Revenue: Property Tax Abatements for Large Businesses and Industry

- Total Revenue Loss for School Districts

- Interactive Dashboard to View Each School District’s Lost Revenue

- Appendix

Quick Overview: School Property Taxes

School districts in South Carolina assess two types of property taxes: one to help cover the cost of school and district operations (in addition to state and federal funding) and the other to pay the debt service for school construction, renovation, and capital equipment. The revenue from each is maintained in totally separate budgets.1 By state law, debt service funds cannot be used for operating expenses such as teachers salaries, instructional supplies, insurance, and utilities.

The full primary-home tax exemption and the tax abatements for large industry and business investments affect school districts in different ways. The tax exemption for primary residences only affects revenue for school operations. Economic development corporate tax abatements affect both operations and construction debt service tax revenue. This white paper focuses on the combined revenue loss for school operations. (Read more about the property taxes you pay, particularly those for schools, in “What to Know about Your Property Taxes” on this website.)

Lost Revenue: Property Tax Exemption for Primary Residence Homes

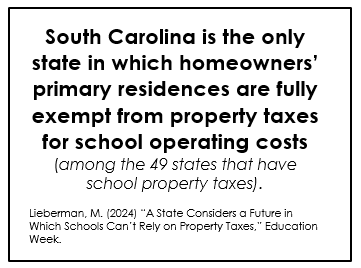

In all but one state (Hawaii), property taxes are a source of revenue for school districts. Among these states, South Carolina is the only one where primary-residence homes are fully exempt from taxes for school operations. This occurred through a combination of state laws the last of which, Act 388, went into effect in 2008.2 (See Appendix for more information.)

As a result, property taxes on your primary home do not help fund the operations of the public schools that your children or your neighbors’ children attend. For additional homes owned locally or elsewhere in the state (like vacation or rental property), the school operations tax provides revenue for the school district in which that home is located.

For primary homes, the only school property tax paid is the one for school construction debt service. For all other property such as businesses, vehicles, second homes, and boats, both types of school taxes (operations and debt service) are paid.

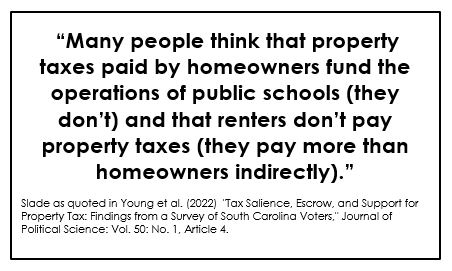

A 2021 survey found that “a majority of South Carolinians are unaware of the Act 388 home tax exemption. When asked whether owner-occupied homes are exempt from school operations taxes, only 21% of survey respondents answered correctly with 44% being unsure. Conversely on a separate question, 63% of respondents answered (incorrectly) that home property taxes currently fund school operations in South Carolina.”3

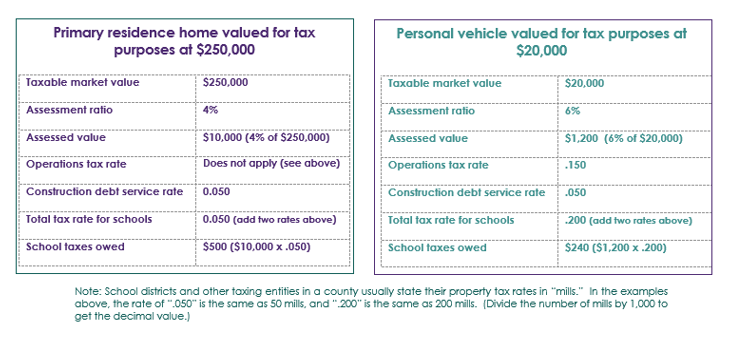

School Property Tax Examples. Below are school property tax examples for a primary residence and a personal vehicle. As shown, the operations tax does not apply to a primary residence, but the .150 tax rate for operations does apply to a personal vehicle.

In the primary residence example, the only school property tax owed is $500 based on a construction debt service tax rate of .050. Again, the operations tax rate of .150 shown for the vehicle does not apply to the primary residence. If the exemption for the school operations property tax was not in place, the total owed would be $2,000 ($1,500 for operations plus $500 for construction debt service). The $1,500 is local revenue the school district does not receive for funding school operations.

Unfair Tax Burden. Because of this exemption, higher tax rates on commercial, industrial, and apartment properties as well as personal vehicles are needed to achieve the same revenue for school districts. Before Act 388, commercial and apartment properties were taxed at about twice the rate for primary-residence property. Since then, their rate has been about three times higher.4 Small businesses especially suffer under this arrangement.

Renters pay more in rent due to the higher school tax rates on apartment properties. This is unfair in two respects. Homeowners are the primary beneficiaries of school spending as higher-achieving schools lead to greater increases in home values. “So, it is fair that they should help pay to operate schools. Second, homeowners typically have higher incomes than renters.”5

State Reimbursement for Lost Revenue. The state compensates school districts for only some of their lost property tax revenue through three types of reimbursements. These result from three separate tax exemption/reimbursement laws: two earlier partial homeowner tax exemptions and then Act 388, which “finished the job” eliminating all remaining property taxes for school operations on a primary home.

The three reimbursements are not set up to cover all of the lost tax revenue. The first two are capped reimbursements which never increase as the tax revenue school districts lose goes up, and the third does increase but is not tied to, nor keeps up with, the lost amount. See the Appendix for a description of the three reimbursement “Tiers.”

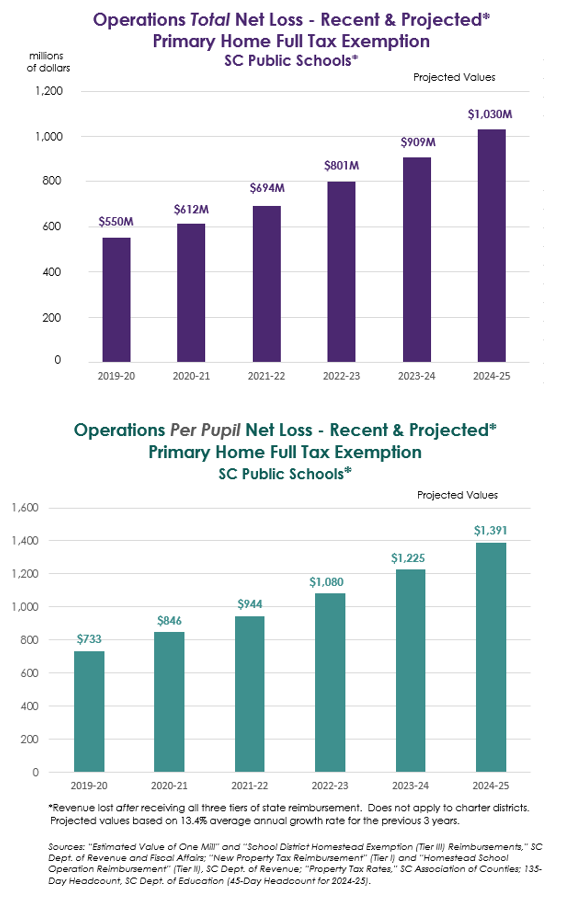

Revenue Lost After State Reimbursements. School Districts are losing a large and growing amount of local revenue for school operations from the primary home full tax exemption. As shown in the first chart below, the total net revenue loss for school districts in the state is currently projected at just over $1 billion per year and growing. This is the revenue loss after receiving the three types of reimbursements from the state. As shown in the second chart below, the current projected per pupil revenue loss for South Carolina public schools is nearly $1,400 per pupil. (None of this affects charter school districts. Local property taxes are not a source of revenue for them.)

Lost Revenue: Property Tax Abatements for Large Businesses and Industry

To attract large corporate investments such as a manufacturing plant or headquarters, state law allows a county council to exempt that property from taxes for a set number of years and instead have it pay a set annual fee. Of the three types of economic development corporate tax abatements in the state, the most commonly known is fee in lieu of taxes or FILOT.

A fuller description of FILOT and descriptions of the two other corporate tax abatement programs–Special Source Revenue Credit (SSRC), and Multi-County Industrial Park (MCIP)—can be found in the Appendix.

The annual tax abatement fees paid by the corporations are less than what would be paid in property taxes, they never go up (like tax revenue can), and can be put in place for extremely long periods of time—up to 40 years. All three types of abatements affect school district tax revenue for both operations and construction debt service. By state law school districts have no say in this, and nothing makes up for their revenue loss, which can continue to increase.

The portion of these fees that counties allocate to school districts depends on the type of tax abatement. For FILOTs the portion of the fees that school districts receive from the county (for both operations and construction debt service) are based on the school district’s tax millage as a percentage of total county tax millage.6 Under a SSRC, fee revenue that would go to a school district can be used by the county for more corporate subsidization.7 For multi-county-industrial-park tax abatements, a county council has full discretion on how much to allocate to a school district although it must allocate some amount.8

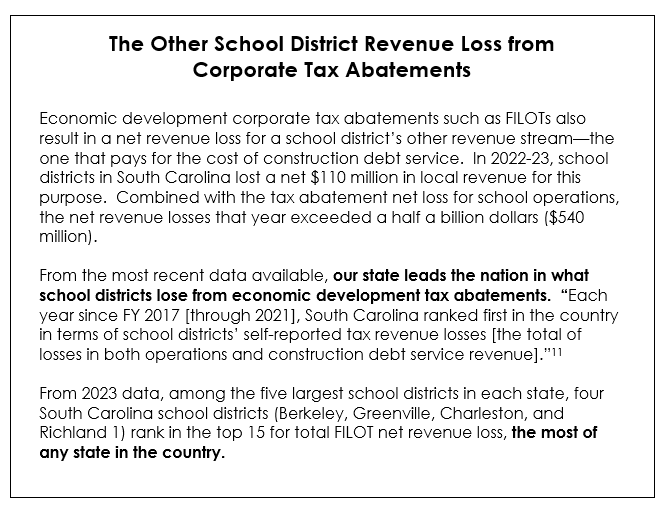

“Even though it is the counties that legally control and award tax abatement agreements with businesses, they lose relatively little compared to school districts.”9 “School districts lose five or six times as much as counties do.”10

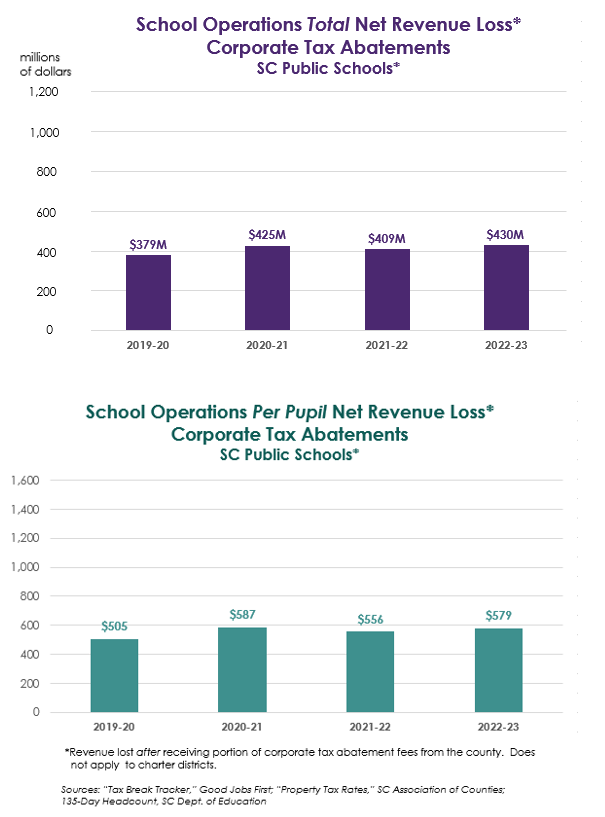

Operations Revenue Lost After Corporate Fee Payments As shown below, assuming no change in recent net revenue losses each year from these tax abatements, school districts in South Carolina are losing around $400 million per year in local revenue for school operations. This equates to around $550 a year on a per pupil basis across all school districts from counties enacting one or more of these state-established tax abatement programs. (None of this affects charter school districts. Local property taxes are not a source of revenue for them.)

Revenue Loss Disproportionately Impacts High-Poverty School Districts. Tax abatement net revenue losses for school operations disproportionately impact high-poverty districts. Among the 20 school districts in South Carolina with the highest per pupil loss in 2023, three-fourths (15) had a poverty rate above the state average of 62%. Of the eight districts with a net pupil loss above $1,000, six had poverty rates above 70%.

Need for Corporate Tax Abatement Programs. A stated reason for needing these programs is that “South Carolina’s effective business property tax rates are high relative to homestead property and neighboring states’ business property taxes.” According to the South Carolina Chamber of Commerce, “fee-in-lieu of property taxes makes it possible for South Carolina county governments to reduce the property tax liabilities of firms that make new investments and create jobs.”12

No Transparency on Specific Deals and the Cost Effectiveness of these Tax Abatements. The state laws for these tax abatements do not include any transparency provisions.13 “The state does not track the costs or benefits of these economic development tax abatements.”14 There are no requirements for counties to report “deal-specific, company-specific information, such as the size of the award, how many jobs were promised and then actually created, what wages and benefits were pledged and then actually paid, or how much capital investment was promised and then delivered.” 15 “Hence, neither policymakers nor taxpayers have any way to assess these costly projects and programs.”16

Total Revenue Loss for Public School Operations in South Carolina

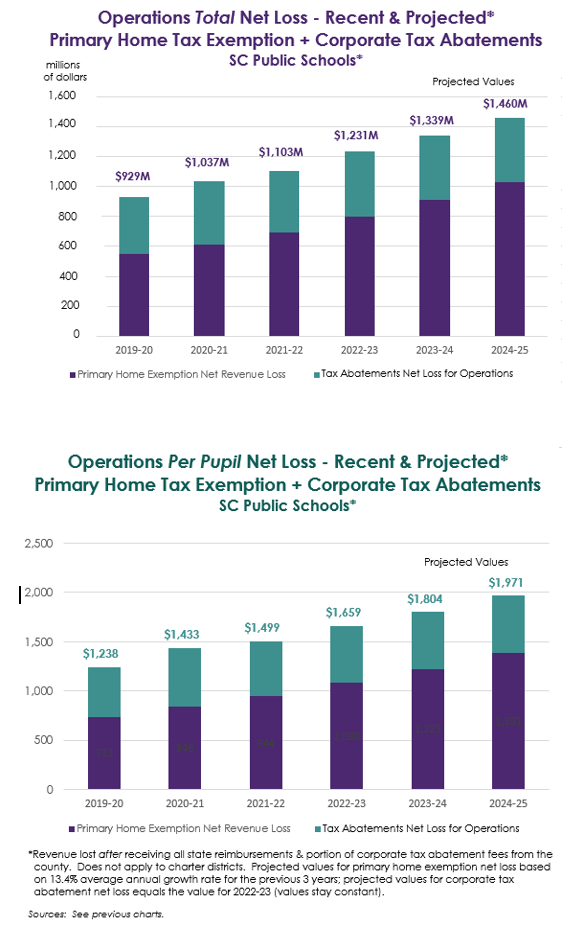

The charts below show the total net operations revenue loss for South Carolina public schools from the primary home full tax exemption and the three types of tax abatements for business and industry. Assuming the total net revenue loss from the tax abatements stays the same and the net loss from the primary home tax exemption continues its growth trend, school districts in South Carolina are losing nearly $1.5 billion a year in local school operations revenue. This revenue loss equates to nearly $2,000 per pupil per year.

Interactive Dashboard to View Each School District’s Lost Revenue

Notes

1National Center for Education Statistics, “Financial Accounting for Local and State School Systems: 2014 Edition, Chapter 6: Account Classification Descriptions — Fund Classifications.”

2South Carolina Chamber Foundation, South Carolina Realtors, and Lincoln Institute of Land Policy (2020) “A Deep Dive on South Carolina’s Property Tax System: Complex, Inequitable and Uncompetitive;” Lieberman, M. (2024) “A State Considers a Future in Which Schools Can’t Rely on Property Taxes,” Education Week.

3Young, Sarah and Thornburg, Matthew P. (2022) “OUR TURN: Act 388’s impact on school taxes largely unknown today, study shows,” Statehouse Report.

4South Carolina Chamber Foundation.

5Ibid.

6Milling, C. (2022), “Opinion of this Office on behalf of Greenwood School District 52,” Office of the South Carolina Attorney General.

7Wen, C., Tarczynska, K., and LeRoy, G. (2020) “The Revenue Impact of Corporate Tax Incentives on South Carolina Public Schools,” Good Jobs First.

8Milling, C.

9Wen, C. (2020)

10Wen, C. (2022) “The Revenue Impact of Corporate Tax Incentives on South Carolina Public Schools 2017-2021,” Good Jobs First.

11Ibid.

12South Carolina Chamber Foundation.

13Gizis, A. (2025) “The Cost of Corporate Tax Breaks to South Carolina Public Schools,” Good Jobs First.

14Wen, 2020.

15Gizis.

16Wen, 2020.

Back to Top

Appendix

- State Reimbursements to School Districts from the Primary Residence Tax Exemption

- How Act 388 Works

- Three South Carolina Economic Development Tax Abatement Programs

- Required Reporting on Revenue Losses from Tax Abatement Programs

1. State Reimbursements to School Districts from the Primary Home Tax Exemption

Capped state reimbursement #1. A state property tax relief bill implemented in 1996 exempted school operations property taxes on the first $100,000 in market value of all primary residential property. Initially, state reimbursement to school districts increased annually. However, since 2002 the reimbursement amount to school districts has been capped. The amount reimbursed to school districts never changes, and the net revenue districts lose increases over time. This is called the “Tier I” reimbursement.

Capped state reimbursement #2. As passed in 1972, homeowners over the age of 65, permanently disabled, or blind receive an exemption on all local property taxes (those for school districts and all other taxing entities in the county). The exemption now covers the first $50,000 in fair market value of their primary residence.

State reimbursements are made to the taxing entities in the county for their lost tax revenue due to this exemption. However, the state reimbursement for lost school operations tax revenue is handled differently than all other reimbursements. The state reimbursement to school districts for lost operations tax revenue was capped in 2008. The amount reimbursed to school districts for lost school operations revenue never changes, and the net revenue districts lose increases over time. This is the “Tier II” reimbursement. For all other local government entities and for school construction debt service, state reimbursements for lost tax revenue are not capped.

Reimbursement #3. Passed in 2006, Act 388 went into effect in 2008 and eliminated school operations property taxes in their entirety for all primary homes. Revenue from a one cent increase in the state sales tax (which does not apply to groceries and some other items; see Appendix.) goes to a fund for reimbursing school districts for the remaining property tax relief beyond Tier I and Tier II. This “Tier III” funding is not a dollar-for-dollar reimbursement for the property tax revenue that school districts lose under this law. Instead increases in reimbursement amounts are based on inflation and population growth. (see “How Act 388 Works” below.)

2. How Act 388 Works

Homeowners do not pay property taxes on their primary residence for school operations.

School districts assess two types of property taxes: one for school operations and the other for school construction debt service. Act 388 eliminated property taxes for school operations on owner-occupied residential property beginning in 2008. School operation property taxes remain in place for all other property including commercial, industrial, vehicles, and second homes. Property taxes for school district construction debt service remain for all types of property.

The state reimburses school districts for lost tax revenue with revenue from one cent of the sales tax.

Revenue from an additional one cent in the state sales tax goes to a fund (the Homestead Exemption Fund) for reimbursing school districts for Act 388 property tax relief—tax relief beyond Tier I and Tier II (see previous section in Appendix). The additional one cent tax applies to all taxable items except groceries, accommodations, and items with a sales tax cap such as automobiles, boats, and aircraft.

There are two types of reimbursement to school districts:

- All school districts receive a reimbursement based on the Act 388 formula (see below).

- Some school districts receive an additional reimbursement to ensure that no county receives less than $2.5 million in property tax reimbursements to school districts in their county. The amount distributed to each school district in the county is based on their proportionate enrollment.

The formula for reimbursing school districts is not a dollar-for-dollar reimbursement.

Under the Act 388 law, in the first year (school year 2007-08) school districts are reimbursed dollar for dollar for their Act 388 (Tier III) lost property tax revenue.

For subsequent years, the distribution to school districts is based on 1) a formula for determining the total statewide amount of money available for all school districts and 2) a second formula specifying how the statewide amount is distributed to each school district.

The total statewide amount equals the first year’s amount of sales tax revenue required for the dollar-for-dollar reimbursement to all school districts increased every year by a percentage equal to the percentage increase in state population plus the rate of inflation.

The amount each school district receives from this statewide fund will be the first year’s dollar-for-dollar reimbursement increased by the district’s proportionate share of the increase in the state-wide amount. A district’s proportion is based on the district’s weighted-pupil enrollment as a percentage of statewide weighted-pupil enrollment plus an add-on weighting for students in poverty.

With this distribution formula, after the first year, Act 388 reimbursement is not a dollar-for-dollar reimbursement for lost local property tax revenue. This discrepancy is even greater when capped Tier I and Tier II reimbursements are included.

If sales tax revenue is not sufficient, state General Fund money must cover the shortfall.

If revenue from the one-cent sales tax is not sufficient to meet the mandatory school district reimbursements under the formula, the additional funds needed to meet this obligation come from money that would otherwise go into the state General Fund annual budget.

For the first thirteen years after the implementation of Act 388, revenue from the one-cent sales tax never met the required amount under the formula. Each year funds were taken from the state General Fund budget to cover the shortfall. The deficits were large. In each of the five years from FY2010 to FY14, the shortfall exceeded $100 million. For the first time in 2021, revenue from the one-cent sales tax exceeded the required amount. In recent years, the annual excess has been over $100 million.

Back to Top

3. Three South Carolina Economic Development Tax Abatement Programs

From Wen, C., Tarczynska, K., and LeRoy, G. (2020) “The Revenue Impact of Corporate Tax Incentives on South Carolina Public Schools,” Good Jobs First; Milling, C. (2022), “Opinion of this Office on behalf of Greenwood School District 52,” Office of the South Carolina Attorney General.

In South Carolina, payments made by businesses in lieu of taxes consist of three programs: Fee in Lieu of Taxes (FILOT), Special Source Revenue Credit (SSRC), and Multi-County Industrial Park (MCIP).

Fee in Lieu of Taxes (FILOT): “FILOT agreements are ubiquitous in South Carolina; almost every school district is affected by them. Established in 1988, the program allows businesses that make a certain minimum investment in a project to negotiate an agreement with the county in which the project is located to pay a fee in lieu of ad valorem property taxes (based on a reduced assessment ratio and fixed millage rate). Under this arrangement, businesses (or “sponsors” in South Carolina laws) receive deep discounts on their property taxes.

FILOT comes in three forms. The first, created in 1988, is intended for very large projects with at least $45 million in new investment. The second form was introduced in 1995 to allow for FILOT agreements for sponsors investing more than $5 million in a project ($1 million in distressed counties) within five years plus up to five years in extension; this investment minimum was halved by a 2006 amendment and has been $2.5 million since. The third form is a simplified FILOT arrangement that does not involve the use of industrial revenue bonds; instead, it allows a sponsor to hold the title of the property and negotiate with the county for a lower assessment ratio and fee payment structure.

FILOT agreements cause revenue losses for localities for years on end. Not only do companies get up to ten years to make the investment, but their FILOTs are far less than they would otherwise pay in property taxes and last for up to 30 years with a possible 10-year extension.

Furthermore, all three versions of the FILOT program have special provisions for “megadeals” (i.e. especially large projects) to extend both the time to complete the project and the length of the property tax discount.” (Wen, 2020)

“For FILOT projects not located in an industrial development park (see section on ‘multi-county industrial parks’ below), distribution of the fee in lieu of taxes on the project must be made in the same manner and proportion that the millage levied for school and other purposes would be distributed if the property were taxable.” (Milling, 2022)

Special Source Revenue Credit (SSRC): “The property tax abatements don’t end with the FILOT program. Under the SSRC program, South Carolina’s counties can use a portion of their FILOT revenues to issue special source revenue bonds. They can then award credits to taxpayers to be applied against their property taxes for acquiring, building, or improving infrastructure or real properties for the purposes of manufacturing located in a multi-county industrial or business park.” In other words, instead of applying those reduced property tax revenues under a FILOT agreement to public education or other services, SSRC allows counties to divert those funds for other uses related to the project. (Wen, 2020)

Multi-County Industrial or Business Park (MCIP or MCBP) Program: “Since 1989, South Carolina’s counties can enter into agreements with contiguous counties (with the consent of encompassed municipalities) to create multi-county industrial or business parks for which revenues and expenses will be shared among the member counties. Counties can designate certain properties to be included in the industrial park and qualify them for SSRC. FILOT projects don’t have to be in an industrial park, but they qualify for additional tax savings if they are.” (Wen, 2020)

“For a project located in an industrial development park, distribution of the fee in lieu of taxes on the project must be made in the manner provided for by the agreement establishing the industrial development park….However, all taxing entities must be allocated some fee in lieu revenue and the amount allocated must be specified in the agreement establishing the multi-county business or industrial park, but no particular allocation method is required.” (Milling, 2022)

4. Required Reporting on Revenue Losses from Tax Abatement Programs

From Wen, C., Tarczynska, K., and LeRoy, G. (2020) “The Revenue Impact of Corporate Tax Incentives on South Carolina Public Schools,” Good Jobs First.

Data on these revenue losses is available to the public because of the 2015 accounting rule, “Governmental Accounting Standards Board (GASB) Statement No. 77 on Tax Abatement Disclosures.” It requires state and local governments, including school districts, that abide by Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) to disclose their revenue losses resulting from economic development tax abatement programs.

“This obligation applies whether the government is the actively granting entity—such as South Carolina’s counties—or a second government that loses revenue passively, such as the state’s school districts. Each jurisdiction reports its own portion of the foregone tax revenue in its audited financial statement, a report of the prior fiscal year’s income and spending.”