What you are paying for in local property taxes is not easy to understand. The sections below are intended to help you gain knowledge about these taxes and specifically those for public schools.

- Introduction

- Two Types of School Property Taxes

- Who Sets School Tax Rates?

- Understanding What You Owe

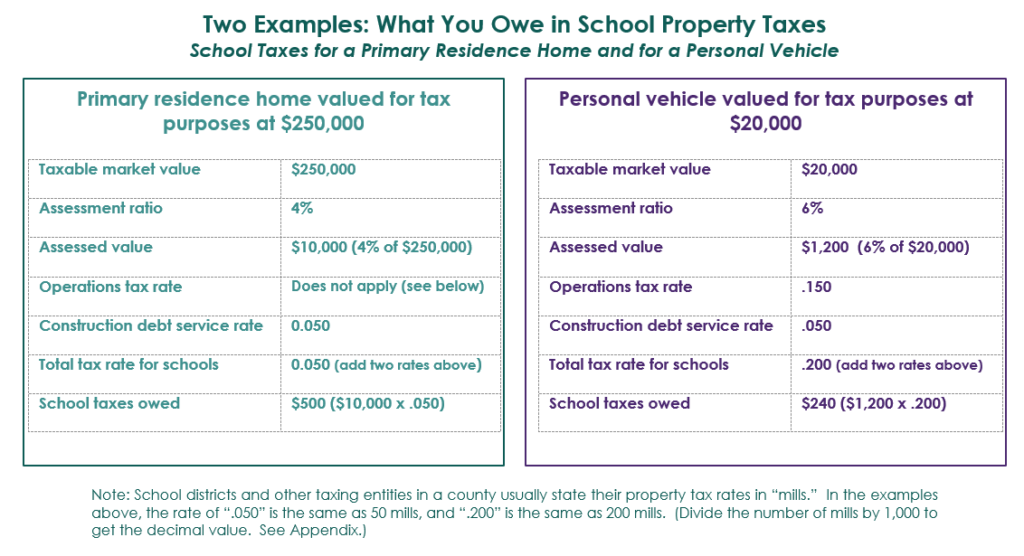

- Two Examples: What You Owe in School Property Taxes

- Major Exemptions to Paying Property Taxes

- Understanding the Tax Bill for a Primary Home

- Appendix

Introduction

Local property taxes are the primary source of revenue school districts have to 1) help cover the cost of teacher salaries and other school and district operational costs and 2) to pay for facility construction and renovation.

Property taxes raise revenue for many other local government entities such as the county, cities, libraries, the technical college, and special purpose districts (such as those for fire and water services).

Individuals in South Carolina pay annual property taxes on property they own such as their home, vehicle(s), boat(s), and any secondary residences. Businesses and corporations also pay annual taxes on their property.

There is a separate annual tax bill for each owned taxable property. For example, the annual tax bill for your personal vehicle includes the property taxes owed for all of the government entities in the county that provide or offer services to the area of the county where you live. The taxes owed are combined into one total amount for payment. For those with a home mortgage, the total home tax amount is paid out of the mortgage escrow account.

Two Types of School Property Taxes

As stated above, school districts assess two types of property taxes: one to help cover the cost of school and district operations and the other for the debt service for school construction and renovation. By state law funds for school operations and for construction debt service must be kept totally separate. Funds cannot be transferred between the two.1

Property Tax for Operations: School district property taxes for operations raise local revenue to cover a significant portion of the expenses to operate individual schools and the district office. This includes salaries for school personnel including teachers, media specialists, counselors, health services staff, principals, and office staff; classroom materials; technology; library books; building maintenance; transportation; and district administration services and salaries.

Again, by state law revenue from this property tax cannot pay for school construction and renovation. This tax rate is likely much higher (even 10 times higher) than the district’s rate for construction debt service. (Find examples in the Finances“ section of “The Data.”)

Property Tax for Construction Debt Service: A separate school district property tax raises revenue to cover debt service payments (principal and interest) for bonds sold to fund construction and renovation projects. With small exceptions (see Appendix for one example), this is the only source of funding districts have to pay for this expense. By selling bonds the cost of these projects can be spread over many years.

Again, revenue from this property tax cannot pay for school and district operations. This tax rate is likely much less than the district’s rate for operations. (Find examples in the Finances section of “The Data.”)

Who Sets School Tax Rates?

A school district’s board of trustees sets the property tax rates for operations and for construction debt service after consideration of rates recommended by district administration to meet funding needs. The rates must comply with state limits.

For the operations tax, the state has set limits on how much a district can increase the rate; for the debt service tax, there is a state limit on the amount of debt that a district can incur. (See Appendix.) Some school districts have full “fiscal autonomy,” and school boards are free to set their own tax rates within these limits. Other districts have “Limited” or “No” fiscal autonomy such that county council must provide final approval of a rate change or must approve the actual district budget including the corresponding rate change.2

Understanding What You Owe

The property taxes you pay on a home, vehicle, business, or other real property are based on the following factors:

- the taxable market value of the property,

- the assessment ratio for that type of property,

- the property’s resulting assessed value, and

- the tax rates of the various taxing entities in your county, including your public school district, that provide or offer services to the area of the county where you live or operate a business.

Taxable market value. The county determines the taxable market value of home and business property. By state law, the county reassesses the value of these types of properties every five years. For homes there is a limit (currently 15%) on how much the value can increase from reassessment (does not apply when a house is sold). For vehicles and boats, taxable values are annually set based on the model and age of the vehicle or boat.

Assessment ratio. The state sets the assessment ratio for each type of property. This is the percentage of a property’s taxable market value to which the property tax will be applied. For primary residence homes the ratio is 4%. For personal vehicles, second homes, and most other personal property the ratio is 6%. This higher assessment ratio also applies to small businesses and rental property.3

Assessed value. The property’s assessed value equals the taxable market value multiplied by the assessment ratio. (See the two examples below concerning the property tax portion for public schools.)

What you owe. The property tax you owe is the assessed value of that property multiplied by the total of all of the different property tax rates.4 (See tax bill examples #1 and #2 further below.) Tax rates on most tax bills are shown as decimal values that represent millage rates set by the taxing entities. (Learn about property tax millage in the Appendix.) Also see the SC Revenue and Fiscal Affairs “Property Tax Frequently Asked Questions.”

Major Exemptions to Paying Property Taxes

Exemption for Primary Residence Homes. Property taxes on your primary home do not help fund the operations of the public schools that your children or your neighbors’ children attend. South Carolina is the only state with this full home tax exemption for school operating costs.5

As shown in the example above, primary-residence homes (“owner-occupied”) are not taxed for school operations due to a state law known as Act 388 that went into effect in 2008. The only school property tax on these homes is the one for school construction debt service. Both types of school taxes are paid on all other property such as businesses, vehicles, second homes, and boats.

Property taxes on your primary home do not help fund the operations of the public schools that your children or your neighbors’ children attend.

In the primary residence example above, the total school property tax owed is $500. If the exemption for the school operations property tax was not in place, the total owed would be $2,000 ($1,500 for operations plus $500 for construction debt service). The $1,500 is revenue the school district does not receive for funding school operations—lost tax revenue for which the state only partially reimburses districts.

Most citizens don’t know that homeowners don’t pay property taxes to fund the operation of their public schools. A 2021 survey found that “a majority of South Carolinians are unaware of the of the Act 388 home tax exemption. When asked whether owner-occupied homes are exempt from school operations taxes, only 21% of survey respondents correctly with 44% being unsure. Conversely on a separate question, 63% of respondents answered (incorrectly) that home property taxes currently fund school operations in South Carolina.” 6

Based on the results of this survey, study authors call for improving homeowner awareness of this tax exemption. Here are two of their recommendations:

- Annual tax bills mailed to homeowners could be formatted to include a short description of the home tax exemption for schools, instead of just listing a line item for a school tax credit on the tax bill.

- Realtors could be instructed to clearly point out the tax exemption for primary residences at point of purchase. At that time homebuyers complete a form to claim their home as a “primary residence.” “They may understand that this assesses their home at a lower percentage while not realizing that this gives them an exemption from home taxes to fund school operations by default.”7

Exemption for Large Businesses and Industry. To attract large corporate investments such as a factory or headquarters, a county council can exempt that property from taxes for a set number of years and instead have it pay a set annual fee. This is called a fee in lieu of taxes or FILOT. The annual fee is less than what would be paid in property taxes, it never goes up (like tax revenue can), and can be set for multiple decades.

This exemption applies to school district tax revenue both for operations and for construction debt service. Nothing makes up for any part of this revenue loss.

Resulting Higher Rates for Other Property. These two tax exemptions require school districts to set higher tax rates on other property like vehicles, rental property, and small businesses (property that already has a higher assessment ratio) to make up some portion of the lost revenue. (Read more about these exemptions and the resulting revenue loss for school districts in the “What’s Trending” post titled “SC School Districts are Losing $1.5 Billion a Year for School Operations.”)

Understanding the Tax Bill for a Primary Home

As stated above, primary residence homes in South Carolina are not assessed property taxes for school operations. The only school property tax assessed for this type of property is the one for construction debt service.

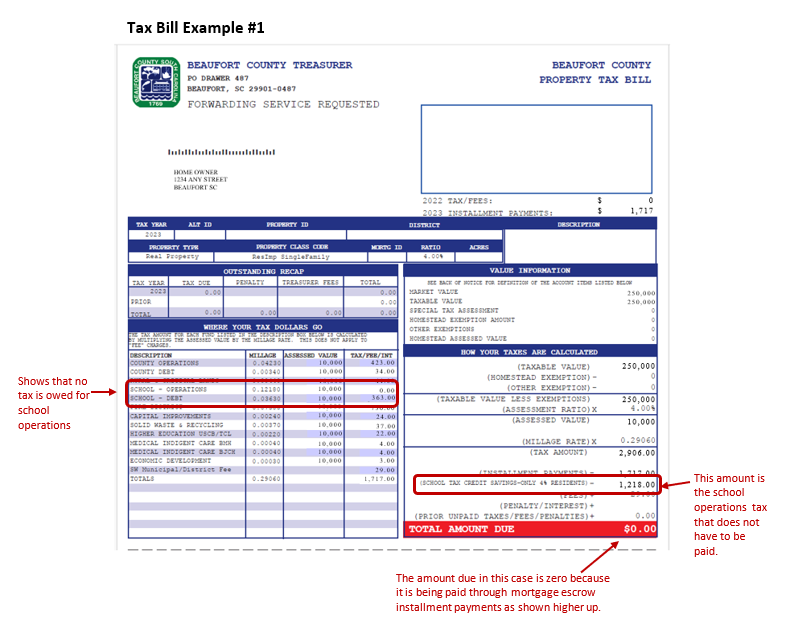

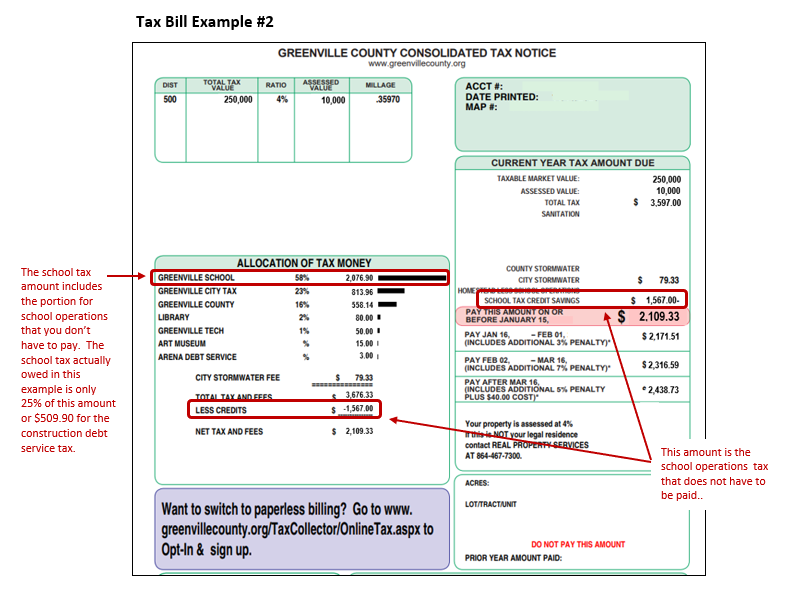

How school property taxes appear on a bill for a primary home vary from county to county in the state. Some bills may show both types of school taxes and indicate that no tax is owed for school operations. It additionally may show the operations tax amount that you did not have to pay.

Other tax bills may not show both types. Instead, the bill may show one amount owed for school taxes, which is a total of the debt service tax actually owed and the operations tax that is not owed. The operations tax amount is shown elsewhere as a “credit” that is removed from the total tax owed.

Here are two example tax bills: one for Beaufort County and one for Greenville County.

Example #1 below shows a tax bill for a $250,000 home in Beaufort County using 2023 rates. On the left, it splits out the two types of school property taxes and shows that the amount owed for the operations property tax is zero. On the right near the bottom, there is a “School Tax Credit Savings – only 4% residents” line showing the school operations tax amount that is not owed.

Example #2 below shows a tax bill for a $250,000 home in Greenville County using 2023 rates. On the left, there is only one school tax line that shows the total of the construction debt service tax actually owed and the tax for operations that is not owed. On the right, there is a “School Tax Credit Savings” line showing the operations property tax amount taken off the bill. This amount also shows as “Less Credits” on the left at the bottom. Nothing on the bill states that you do not owe the tax for school operations.

This type of bill does not separate out the tax for operations and the tax for construction debt service. Instead it shows one figure that includes the operations tax that does not have to be paid. A homeowner may only notice the “Greenville School” tax line in the left-side column and not the credit for the tax relief and have no idea that they don’t pay property taxes to fund the operations of their public schools.

Thus what appears owed for school taxes is much higher than what it actually is. In the Greenville County example for 2023, the not-owed tax amount for school operations made up 75% of the “Greenville School” amount listed on the bill. In this example, instead of owing the $2,076.90 shown for school taxes, the actual amount owed is $509.90.

In both tax bill examples, taxpayers are not provided with the information needed to clearly understand the tax relief taking place. “School Tax Credit Savings “does not define what the school property tax relief is, or explain why it has been applied. Homeowners who pay taxes through a mortgage escrow account may not even review their annual tax bill given that their mortgage servicer remits the tax payment on their behalf.8

Notes

1National Center for Education Statistics, “Financial Accounting for Local and State School Systems: 2014 Edition, Chapter 6: Account Classification Descriptions — Fund Classifications.”

2South Carolina Association of School Board Officials, “Setting Debt and Operations Millage: Role of County Auditors,” Spring 2021 Conference, March 3, 2021.

3South Carolina Dept. of Revenue, “Find Property Assessment Ratios.”

4South Carolina Dept. of Revenue, “Individual Property Tax,” July 2023.

5South Carolina Chamber Foundation, South Carolina Realtors, and Lincoln Institute of Land Policy (2020) “A Deep Dive on South Carolina’s Property Tax System: Complex, Inequitable and Uncompetitive.”

6Young, Sarah and Thornburg, Matthew P. (2022) “OUR TURN: Act 388’s impact on school taxes largely unknown today, study shows,” Statehouse Report.

7Young, Sarah. and Thornburg, Matthew P. (2022) “ Findings of the 2021 South Carolina Citizen School Tax Survey: A Report by the University of South Carolina Aiken’s Social Science and Business,” USC Aiken.

8Ibid.

Appendix

- Property Tax Millage

- Revenue Gained from One Mill in Taxes

- Maximum Allowable Increase in the Millage Rate for School Operations

- Limit on the Millage Rate for School Construction Debt Service

- Reassessment: Impact on Operations and Debt Service Tax Rates

- Sales Tax for Construction Debt Service Available to Some School Districts

1. Property Tax Millage

Property tax rates are set as a number of “mills” and usually stated to the public in number of mills by school districts and other taxing entities in a county. One mill is equal to $1 of tax for every $1,000 of a property’s assessed value, which is a small percentage of its market value. (See “Understanding What You Owe” above for further explanation of “assessed value.”)

However, on many property tax bills, the tax rate is stated as a decimal value. To translate, 1 mill is the same as a tax rate of .001 and 200 mills is a rate of .200. For example, if the assessed value of a property is $10,000 and the millage is 200, the tax owed is $2,000 (10,000 x 0.200).

2. Revenue Gained from One Mill in Taxes

The revenue gained by a taxing entity from one mill in taxes depends on the total assessed value of taxable property in that entity’s jurisdiction.

Greater taxable property wealth results in a higher assessed value and a larger amount of revenue that can be raised from each property tax mill. The higher the property wealth, the lower tax rates need to be to raise a certain amount of revenue. The lower the property wealth, the higher the tax rates need to be.

Not surprisingly, there are wide disparities in school district property wealth even among districts in the same county. This affects what millage rates the school districts need to impose to raise a certain amount of revenue.

A tax entity’s mill value equals the total assessed property value in the jurisdiction divided by 1,000. For example, if the total assessed value for a school district’s operations tax is $236,159,000, the value of a mill is determined by dividing this number by 1,000, which in this case results in an operations mill value of $236,159. Each property tax mill levied for school operations would generate $236,159 in revenue. (See school district mill values at the “School District Property Tax Rates” dashboard in the Finances section of “The Data.”)

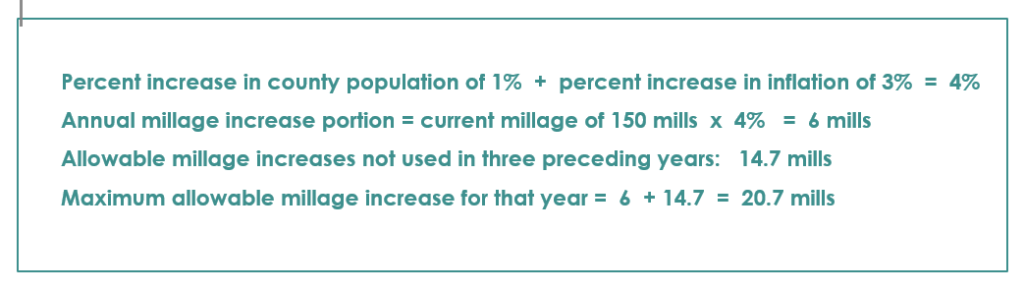

3. Maximum Allowable Increase in the Millage Rate for School Operations

Set by the state, there is a limit on how much a school district can increase the operations tax millage in a year. It is based on the annual portion of the allowable millage increase and the allowable millage increases not used in the three preceding years. Here is how the maximum allowable millage increase is computed:

Annual Portion of the Allowable Millage Increase =

(Percent increase in county population + Percent increase in inflation)* x Current millage rate

Total Allowable Millage Increase for that Year =

Annual millage increase portion + allowable millage increases not used in the three preceding years

*percentages are those for the preceding calendar year

Example: Calculation of the Total Allowable Millage Increase for a Year

4. Limit on the Millage Rate for School Construction Debt Service

School districts set the construction debt service millage at the level needed to service the amount of debt. The limitation on increases to this millage results from the maximum amount of debt a school district in the state can have at any one time as set by the South Carolina constitution: school district indebtedness cannot exceed 8% of the assessed value of the taxable property in the district.

5. Reassessment: Impact on Operations and Debt Service Tax Rates

State law requires each county to reassess all real property every five years. Once completed, millage rates for each taxing entity (county, city, school district, etc.) are adjusted such that the revenue generated by each property tax remains the same. This applies to both school district operations and construction debt service property taxes. In most cases, the assessed value for the tax goes up and the millage rate goes down. The last reassessment was in 2021, a delay of one year due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

6. Sales Tax for Construction Debt Service Available to Some School Districts

Through county referendum, some school districts have the ability to assess a one percent sales and use tax for specific education capital improvement purposes listed in the referendum question. At least ten percent of the revenue from this tax must be used to provide a nonrefundable credit against existing debt service taxes. Any remaining amount can pay the debt service for specific, capital improvements listed in the referendum question.

School districts eligible to impose this tax must be located in a county meeting one of these two criteria:

- The county collected at least seven million dollars in state accommodations taxes in the most recent fiscal year (Once a county meets this threshold the district thereafter remains eligible to impose this tax.),

OR

- No portion of the county in which the tax is to be imposed is subject to more than a two percent total local sales tax; and

the county in which the tax is to be imposed is encompassed completely by one entire school district, and that school district also extends into one adjacent county.

(Source: Education Capital Improvements Sales and Use Tax, SC Code of Laws, Article 4, sections 4-10-410 and 4-10-470.)

See the counties with this sales and use tax.

20250717