Sections

- A Teacher’s Workday

- A Teacher’s Classroom

- Teacher Stress

- Impact of the Pandemic

- Addressing Teacher Wellness

- What Teachers Want

- Work Conditions Particular to Teachers of Color

- Why Teachers Leave

- Impact on Students from Teacher Stress and Attrition

- Why People Choose to be a Teacher

- Why Teachers Stay

A Teacher’s Workday

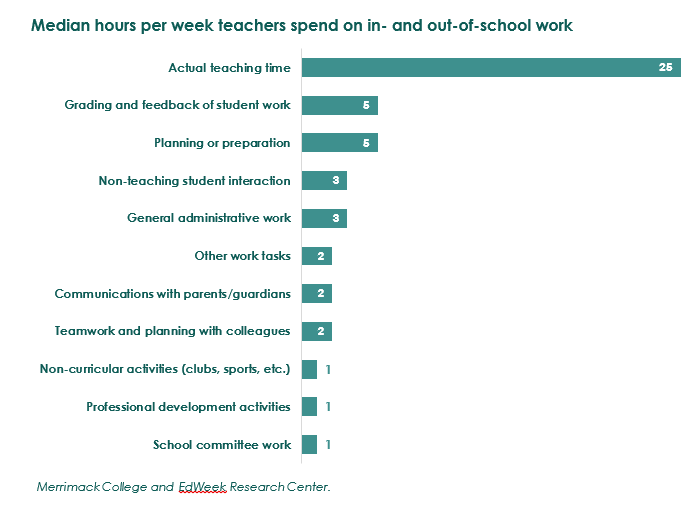

From a 2023 national survey, teachers on average work 53 hours per week during the school year (7 more hours per week on average than working adults as a whole). Of the surveyed teachers, nearly half said they work more than 50 hours per week, and 16% said they work more than 60 hours per week.1

Just under half of that time (25 hours) is spent directly teaching students. From a 2022 national survey, most teachers say they’d like to spend more time on activities directly related to teaching (planning, instruction) and less time on more ancillary tasks (administrative work, non-teaching student interactions such as hall duty, mentoring, and counseling.)2

A Teacher’s Classroom

A teacher can face many challenges in her/his classroom due to the circumstances of student’s lives. Students come to school from a wide-range of situations that can impact their behavior, performance and achievement. “A student’s social environments, their neighborhoods, their parents’ educational attainment and employment status, and their access to health services and nutritious food can all have an effect.“3

We continue to rely on schools to make up for a broad array of missing or inadequate financial, material, and relational supports … without providing schools with the resources necessary to address all those needs.

Southern Education Foundation

Students in these types of circumstances are most prevalent in schools with a high rate of students in poverty. Two out of three public schools in South Carolina (69%) have 60% or more of their students from impoverished households. Among all school levels, the percentage of elementary schools is highest at 72%.4

The result is often a high level of classroom challenges. Of South Carolina teachers in a 2013 survey:

- 99% have at least one student who needs assistance or intervention for social, emotional or behavioral challenges.

- 76% have student reading levels that span four or more grades.

- 66% have students who are working two or more grades below grade level.

- 61% have special education students in their classroom.

- 55% have students who are gifted or who are working significantly above grade level.

- 44% have English Language Learners in their classroom.5

The Southern Education Foundation states, “We continue to rely on schools to make up for a broad array of missing or inadequate financial, material, and relational supports…without providing schools with the funding and resources necessary to address all those needs.”6

Teacher Stress

Today, teaching is one of the most stressful occupations in the U.S.7 And teachers experiencing exhaustion and burnout related to their work are likely to have a number of negative physical and psychological symptoms and consequences.8 In a recent survey of South Carolina teachers, more than 60% reported that they mostly or always feel used up by the end of the workday and feel emotionally drained from their work.”9

A recent study of teacher mental health in New Orleans found that “more than a third of educators met the threshold for a diagnosis of depression or anxiety, with one in five exhibiting significant symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder. Teachers also reported rates of emotional distress that were similar to or higher than those of health care workers.”10

Teachers and other school staff who work closely with traumatized children are at risk of secondary traumatic stress. “The impact of compassion fatigue may be particularly acute for teachers working in poor, under-resourced urban and rural communities, where students may have been exposed to community and family violence and traumatic experiences.”11

The New Orleans study found that teachers’ mental health is closely linked to how effective they feel in the classroom. Self-efficacy was found to buffer against a lot of trauma impacts and burnout. The report further states, “If teachers are feeling efficacious, if they feel like ‘I’m doing my job and doing it well,’ those are good signs in terms of their willingness to stay in the profession.”12

Impact of the Pandemic

Many of these challenges greatly increased recently due to the effects of the pandemic. This includes a high level of additional instructional work due to extended time out of the classroom for both students and teachers; a higher number of learning levels in a classroom; increased social, emotional and mental health needs of students and teachers; and staff shortages of substitutes and other school staff.

Extended Time Out of the Classroom for Both Students and Teachers. Since schools have re-opened, the isolation and quarantine of students and teachers due to Covid has resulted in long stretches of time out of the classroom. Helping students catch up from these extended periods of lost learning has been an additional challenge for teachers as was making up instruction due to their own bouts of Covid.

Higher Number of Learning Levels in a Classroom. Another impact of the pandemic on teaching has been the exacerbation of the racial and socioeconomic achievement gaps with the historically underserved falling further behind academically while more privileged kids moved farther ahead.

This can mean an increase in the number of learning levels represented in a single classroom requiring teachers to further differentiate instruction. Before pandemic-related school closures, a single classroom could have students working at up to seven grade levels. Researchers predicted that when schools re-opened the array of abilities in a classroom could have widened by two or more grades.13

Increased Social, Emotional and Mental Health Needs of Students and Teachers. The American Psychological Association states that after two full years of the Covid pandemic and various traumas endured during that time, mental illness and the demand for psychological services are at all-time high among children as well as adults.14

In a 2022 nationally representative survey, 80% of educators said that their students’ social skills and emotional maturity levels are somewhat or much less advanced now than they were in 2019.15

Experts say teachers need to be prepared for these issues to persist for several years and to be equipped to understand and identify mental health issues in their students.16

Staff Shortages. School districts have faced severe shortages of substitutes and in many other key positions adding more work to educators’ already full plates. Nationwide, teachers have been asked to give up their prep times or professional learning days to cover classes or are adding extra students to their classrooms.17

Resulting Burnout. Operating schools under these conditions has led to burnout among teachers and other staff members. Ninety percent of teachers in a January 2022 National Education Association poll described burnout as a serious problem, largely because of the pandemic and related staffing shortages.

As a result, teachers commonly found that “they have a harder time sleeping, they’re less able to enjoy their free time with family or friends, and their physical health suffers.” As one teacher in the poll stated, “The pay check does not match the amount of workload we are given and the overtime we work to try and complete it all.”18

Addressing Teacher Wellness

Efforts to address teacher wellness are improving. There are a number of “core wellness components and standards that have been established specifically for educator wellness initiatives.19 And research has found several programs and policies that have “shown promise in reducing teacher stress and promoting their social-emotional competencies, well-being, health and performance.”20 This paper does not cover these research findings nor the teacher wellness programming and services provided by school districts in the state or by Public Education Partners Greenville County

What Teachers Want

A 2022 national teacher survey found that 56% of teachers say they are satisfied (very or somewhat) with their jobs. However, the percentage “very satisfied” with their jobs has declined from 62% in 2008 to 12% in this most recent survey.21

From this survey and recent research on teacher work conditions, four areas are among those most important to teacher well-being and satisfaction: positive school social conditions; autonomy; community respect and appreciation; and commensurate pay.

Positive School Social Conditions. Research has found that social conditions in a school—the school’s culture, the principal’s leadership, and relationships among colleagues—best predict a teacher’s job satisfaction and career plans. Importantly, this finding is independent of the background and demographics of students enrolled.

This research defines the elements as follows:

- School culture: school environments are characterized by mutual trust, respect, openness, and commitment to student achievement;

- Principal’s leadership: school leaders are supportive of teachers and create school environments conducive to learning;

- Collegial relationships: teachers have productive working relationships with their colleagues.22

Johnson, Kraft, and Papay, Brown University

It is the social conditions in the school—it’s culture, the principal’s leadership, and relationships among colleagues—that best predict teachers’ job satisfaction and career plans.

Autonomy. In the 2022 survey, autonomy was said to be a key indicator of job satisfaction. Teachers experience less burnout and stress, higher levels of morale and lower turnover rates when they have more control over their work environments—more autonomy over their classroom and collective influence over school policy.

While teachers, nationally, express strong rates of autonomy in many classroom-related areas, they “often feel micromanaged and left out of the decision-making rooms.”23 Schools where teachers feel heard and have influence in decision making are places more likely to retain their teachers.24

Nationally,

- 85% of teachers say they have control over their teaching/pedagogy;

- 75% …over students’ classroom behavior;

- 57% …over the curriculum they teach;

- 36% …over their schedule; and

- 33% …over their school’s policies25

According to Linda Darling-Hammond, President and CEO of the Learning Policy Institute, a more flexible schedule is a particularly key area for improving teacher morale. “Teachers in the U.S. have some of the world’s most-rigorous schedules with classes packed back to back and little time allotted for planning and breaks…More flexible schedules could mean more time for one-on-one meetings, planning periods and home visits…More flexibility also means more time for teachers to be able to listen to their students and have a better sense of their needs. It will ultimately improve morale for those in the profession.”26

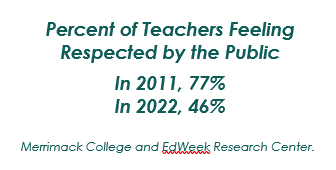

Community Respect and Appreciation. A consistent finding in the research is that teacher job satisfaction is linked to their sense of being respected. However, there is a growing perception among teachers that the general public does not understand or appreciate their work. A 2022 national survey, found that just 46% of teachers felt that the general public respected them and saw them as professionals versus 77% in a 2011 survey.

As one teacher surveyed expressed, “I feel that the media, parents, and even some students feel that they can speak to our situation without even having a true sense of what massive amounts of work we do.”27

Commensurate Pay. Salaries are another reason many teachers are dissatisfied. Most teachers feel underpaid. In a national survey only 34% of teachers said that their base salary was adequate, compared with 61% of working adults.28

Nationally, the average teacher pay has failed to keep up with inflation over the past decade. Adjusted for inflation, teachers in 2021-22 made $3,644 less than they did a decade earlier.29 The South Carolina inflation-adjusted average teacher salary in 2022-23 was $3,925 (6%) lower than it was a decade earlier.

In terms of state minimum salaries in South Carolina, the adjusted, the first-year-teaching, minimum salary in 2023-24 was basically the same ($300 higher) as it was five years before. The same is true for a teacher with a master’s degree and ten years of experience where the adjusted minimum was $120 less than five years earlier. At higher levels of experience, the adjusted state minimums have fallen. At 15 and 20 years of experience with a Master’s, the inflation-adjusted salary was around a $1,000 lower than five years earlier. 30

When including benefits, the advantage in this area for teachers has not been enough to offset the growing wage penalty compared to college graduates working in other professions. Nationally, the teacher total compensation penalty was 17% in 2022 (a 26% wage penalty offset by a 9% benefits advantage). In South Carolina, the weekly teacher wage penalty was 9% in 2022—third lowest in the country.31

A further inequity is the classroom supplies that teachers pay for out of their own pocket. During the 2019-20 school year, South Carolina teachers on average spent $440 of their own money on classroom supplies that wasn’t reimbursed. This amount is above the $275 the state provided to each teacher that year for school supplies—an amount that had not changed for over a decade. The state classroom supplies reimbursement finally was increased starting with the 2022-23 school year when it was bumped up to $300. For 2023-24 the reimbursement was $350. One or more additional increases appear likely.32

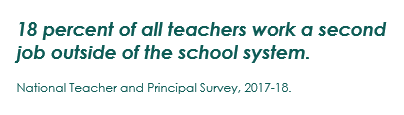

To make up for insufficient pay, a majority of teachers in the country earn income beyond their teaching salary with many taking on coaching or other additional school responsibilities and some (18% of all teachers) working a second job outside of the school system.33 Teachers at the lowest end of the salary scale are the most likely to supplement their teacher pay with outside earnings. They are also more likely to quit their jobs.

In a recent sample exit survey of South Carolina teachers, 80% of those who left the profession “cited salary as the main factor in considering a return to the classroom.”34

For more information on teacher salaries, see the “Teacher Salaries” Closer Look in “Learn More” on this website.

Work Conditions Particular to Teachers of Color

Teachers of color face additional challenges that affect morale and their likelihood of staying in the profession.

Isolation. A teacher participating in a national survey stated: “On a day-to-day basis, it can be a little isolating to be a teacher of color…whether it’s the curriculum I teach, or my own background, oftentimes it’s not in connection with the other teachers…making friends can be a little more difficult.”35

Unpaid Roles Outside Their Job Description. Nationally, it’s been found that teachers of color can experience an “invisible tax” in which they’re asked to “take on unpaid roles that are outside the job they were hired to do, such as translating for parents who speak other languages, acting as school disciplinarians, or serving as mentors for students from their backgrounds.”

Racial Bias From Colleagues. Teachers of color can and do face racial bias and racism—”both in terms of choices of policy, but also in terms of the ways it’s expressed by colleagues, especially white colleagues.”36 According to a 2022 RAND survey, one-third of teachers of color experienced harassment at school because of their race or ethnicity on the job in the last year.37 “Fifty-six percent of teachers who experienced such discrimination pointed to fellow staff as the culprits.”38

Social Justice Imperative. Many feel a sense of responsibility to themselves, their students, and their communities to lead conversations about race and racism while balancing the right amount of pushing for social change and fighting for what’s right and not trying to burn out.

As a society, we show we value education not by calling teachers heroes while treating their work as expendable. We do it by paying attention to the conditions that make teaching and learning possible and by ensuring that — despite everything else happening in the world — schools are sites of stability, not chaos.

Cucchiara, M. B., New York Times opinion, March 8, 2022

Stress of Being Hyper-visible or Invisible. “Teachers of color may find themselves in situations at their schools where they feel hyper-visible or invisible. Either one can result in increased anxiety and stress affecting their engagement and drive.”39

Initial Work Conditions that are Often Additionally Challenging. For many teachers of color their first job is in schools serving more economically disadvantaged and historically marginalized students. Such conditions can result in a higher risk of burnout and attrition from the profession.40

Why Teachers Leave

“Stress is the most common reason for leaving public school teaching early—almost twice as common as insufficient pay.” This is supported by the fact that “a majority of those leaving early take jobs with either less or around equal pay, and three in ten go on to work at a job with no health insurance or retirement benefits.”42

Here are some comments from teachers participating in a 2022 national survey:

- “We cannot continue in this way…we are tired”

- “There is no work-life balance when you are a teacher.”43

- “We’re not complaining, we are hurting… Teachers truly, truly love their jobs. It’s sad to see how many of us are so disillusioned with it all.”

- I think the pandemic has dampened that joy [of teaching], and people are trying to find it again.”44

“Exiting teachers are dissatisfied with their jobs with most citing a variety of school and working conditions, including salaries, classroom resources, student misbehavior, accountability, opportunities for development, input into decision making, and school leadership.”45 These have only been exacerbated by the pandemic with growing workloads and more students having greater academic and social-emotional needs than ever before.46

Teachers are alarmed and have indicated that the burnout crisis in teaching is “a culmination of long-term factors” and “could take a toll on the profession’s ability to sustain itself in the future.”47

Despite the stress and desire to leave, far fewer actually leave than indicate they want to. From 2011 to 2022, the percentage of teachers saying they were very or fairly likely to leave the profession to pursue a different occupation rose from 29 to 44 percent. However, prior to the pandemic, about 8 percent of teachers left the profession annually.48

“Many teachers who say they’re considering leaving won’t actually do so because they can’t afford to lose their pay and benefits.” Older teachers may decide they’re close enough to a pension to hang on.49 “Health-care needs, family responsibilities, and the need for a transition plan are all reasons teachers identify for postponing a career exit.”50

Impact on Students from Teacher Stress and Attrition

Stress and burnout in teaching have a negative impact on the quality of instruction, classroom management, creation of a safe and stimulating classroom climate for students, and relationships with students resulting in lower achievement for students.51 “Teacher burnout appears to affect the stress and motivation levels of the students they teach.”52

Accordingly, a supportive teaching environment contributes to improved student achievement. Research has found that “favorable conditions of work predict higher rates of student academic growth even when comparing schools serving demographically similar groups of students.”53

Teacher attrition has its own negative impact on student achievement. In a New York City study, higher teacher turnover led to lower fourth and fifth grade student achievement in both math and language arts. While this impact is found across all student populations, turnover in the New York City study was particularly harmful to lower-performing students.

“…it’s worth emphasizing that a system that burns out teachers harms young people as well…”

R.A. Brosbe, The Educators Room

Because turnover occurs at a higher rate at higher poverty schools, inequity in education is increased. “It leads to long-term destabilization of low-income neighborhood schools which lose continuity in relationships between teachers, students, parents and community.”54

Stress and attrition also result in higher costs for school districts who need to screen and hire their replacements.55 “Urban districts, on average, spend more than $20,000 on each new hire, including school and district expenses related to separation, recruitment, hiring, and training. These investments don’t pay their full dividend when teachers leave within 1 or 2 years after being hired.”56 And funds spent replacing teachers are not available for improving student learning and the teacher work environment.57

Why People Choose to Become a Teacher

There are several, major reasons for going into teaching The reasons most cited from a survey of teachers were “to make a difference in children’s lives (86%), to share their love of learning and teaching with others (75%), to help students reach their full potential (69%) and to be a part of those ‘aha’ moments when things ‘click’ for a student (65%).”58

Here are the voices of three aspiring teachers:

- I’ve always said I don’t want to go to a job where it’s just the same thing every single day. With teaching, every day is a new day, and no day is gonna be the same day. You have new experiences, and you have new challenges to overcome. That’s something I’m really, really excited for.

- I didn’t really have a lot of teachers of color really until high school. When I was introduced to that, I was like, OK, I can see myself doing this. I did a lot of work in my high school teaching classes learning about the lack of Black educators in the classroom, specifically Black male educators. I found out that students of color are able to work better with seeing representation in the classroom. I just want to be a source of inspiration and motivation for students of color.

- I’ve always wanted to be a teacher. I just really love working with kids, and I feel like their minds at [elementary] age are so malleable…I just feel like my calling is to work with the younger kids and shape their minds while they’re starting to learn and be in school…I don’t think that you’ll really make the kind of difference that you are able to make in the world if you’re doing something that you don’t love doing.59

Why Teachers Stay

A Greenville County Schools Teacher –

My reason for teaching is knowing I make a difference in a student’s life every day. Educators are the very people who can pull a student from the mire of negativity or the cycle of feeling like a failure. I have the opportunity to be an encourager, counselor, school mom, friend, role model, and educator all at the same time. I have heard many of my students say that my classroom is like a safe haven. That safety makes me feel like students enjoy being in my classroom and if they are comfortable, they will want to learn.60

A High School Teacher in New Mexico –

It’s always the kids who keep me hopeful. Your job as an educator is to make sure that it’s a comfortable learning environment for them, that they feel like they can be themselves, that they feel like it’s a safe place for them to come in and grow as an individual—on all levels of their lives, emotionally as well as academically. That’s always what keeps me going and pushes me forward, is just knowing that you have that opportunity, that blessing to have an impact.

A Teacher On Getting Through the Pandemic –

You know, some students lost loved ones, had family members who were in the hospital for long periods of time. What they were facing, they brought that into the classroom. And teachers had an opportunity to extend grace and make accommodations…to be interested in someone’s background and their story and what was happening to them, and let that inform our decisions. I know that in my school, that’s what the adults did. Kids are going to treat people the way they’re treated. And we had the opportunity to show them how to do that.61

Notes

1Steiner, E., et al., (2023), “All Work and No Pay – Teachers’ Perceptions of Their Pay and Hours Worked: Findings from the 2023 State of the American Teacher Survey,” RAND Corporation.

2Merrimack College and EdWeek Research Center. (2022) 1st Annual Merrimack College Teacher Survey: 2022 Results.

3Southern Education Foundation. (2022) Economic Vitality and Education in the South. Part I: The South’s Pre-Pandemic Position.

4InformEdsc from the South Carolina Dept. of Education “Poverty Index.”

5Scholastic Inc. and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. (2013) Primary Sources: America’s Teachers on Teaching in an Era of Change, Third Edition.

6 Southern Education Foundation.

7Greenberg MT, Brown JL, and Abenavoli RM. (2016) Teacher Stress and Health Effects on Teachers, Students, and Schools. The Pennsylvania State University.

8Lever N., Mathis, E. and Mayworm A. (2017) School Mental Health Is Not Just for Students: Why Teacher and School Staff Wellness Matters. Rep Emot Behav Disord Youth. 2017 Winter; 17(1): 6–12.

9Berry, B., Hamm, D. and Snyder, L., (2022) “The Future of South Carolina’s Teaching Profession: Addressing Teacher Shortages & Accelerating Student-Led Learning,” ALL4SC.

10Hawkins, Beth. (2020) “New Research Predicts Steep COVID Learning Losses Will Widen Already Dramatic Achievement Gaps Within Classrooms.”

11Lever.

12 Hawkins.

13 American Psychological Association. (2020) “Psychology’s Understanding of the Challenges Related to the COVID-19 Global Pandemic in the United States.;” Fay, Laura. (2020) “New Data Suggest Pandemic May Not Just Be Leaving Low-Income Students Behind; It May Be Propelling Wealthier Ones Even Further Ahead;” Hawkins; and Kuhfeld, M.; Soland, J.; Tarasawa,B.; Johnson, A.; Ruzek, E.; and Liu, J. (2020). Projecting the potential impacts of COVID-19 school closures on academic achievement. (EdWorkingPaper: 20-226). Retrieved from Annenberg Institute at Brown University.

14 Abramson, Ashley. (2022). “Children’s mental health is in crisis. As pandemic stressors continue, kids’ mental health needs to be addressed in schools.” American Psychological Association 2022 Trends Report. Vol. 53 No. 1.

15 Sparks, Sarah D. (2022) “How Schools Use Covey’s ‘7 Habits of Highly Effective People’.” Education Week.

16 Will, Madeline. (2021) “The Teaching Profession in 2021 (in Charts).” Education Week.

17Ibid.

18Will (2021) and Heubeck, Elizabeth. (2022) “Side Hustles and Second Jobs: Teachers Still Feel Pressure to Earn More Money.” Education Week.

19Lever.

20Greenberg.

21Merrimack College.

22Johnson SM, Kraft MA, Papay JP. How context matters in high-need schools: The effects of teachers’ working conditions on their professional satisfaction and their students’ achievement. Teachers College Record [Internet]. 2012;114 (10) :1-39.

23Lever; Merrimack College; and Will, Madeline. (2022) “Teacher Job Satisfaction Hits an All-Time Low. Exclusive new data paints a picture of a profession in crisis.” Education Week.

24Bartlett, Lora. (2021) “Will the Pandemic Drive Teachers Out of the Profession? What One Study Says.” Education Week.

25Merrimack College.

26Stanford, Libby. (2022) “With Teacher Morale in the Tank, What’s the Right Formula to Turn It Around?” Education Week.

27Merrimack College.

28Steiner..

29“Educator Pay Data,” National Education Association.

30InformEdsc.org.

31Allegretto, S., (2023) “Teacher pay penalty still looms large: Trends in teacher wages and compensation through 2022,” Economic Policy Institute.

32Garcia, E. et al., (2023) “Underpaid and Undersupplied: The Hidden Costs of Teaching in America,” Learning Policy Institute; and “General Appropriations Bills, Part 1B, Section 1A-EIA,” South Carolina General Assembly.

33Heubeck ;and Will, Madeline, (2020) “Still Mostly White and Female: New Federal Data on the Teaching Profession,” Education Week.

34Berry, B., Hamm, D. and Snyder, L., “The Future of South Carolina’s Teaching Profession: Addressing Teacher Shortages & Accelerating Student-Led Learning,” ALL4SC, 2022.

35 Will, Madeline, (2020) “’No One Else Is Going to Step Up’: In a Time of Racial Reckoning, Teachers of Color Feel the Pressure,” Education Week.

36Ibid.

37Steiner, Elizabeth D., Doan, Sy, et al., (2022) “Educators Are Twice As Stressed As Other Working Adults.” The State of the American Teacher and the American Principal. RAND Corp.

38 Will, Madeline., (2022) “Stress, Burnout, Depression: Teachers and Principals Are Not Doing Well, New Data Confirm.” Education Week.

39Will, “No One Else is Going to Step Up…”

40Gershenson, S., Hansen, M., and Lindsay, C. (2021) Teacher Diversity and Student Success: Why Racial Representation Matters in the Classroom. Harvard Education Press.

41omitted

42 Diliberti, M.K.; Schwartz, H.L..; Grant, D.. (2021) “Stress Topped the Reasons Why Public School Teachers Quit, Even Before COVID-19,” RAND Corporation.

43Merrimack College.

44 Will. “Teacher Job Satisfaction Hits an All-Time Low…”

45 Ingersoll, R.; Merrill, E.; Stuckey, D.; Collins, G.; Harrison, B. (2021) The Demographic Transformation of the Teaching Force in the United States. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 234.

46 Will, “Teacher Job Satisfaction Hits an All-Time Low…”

47Brosbe, Ruben A. (2022) “Teaching Was Never Sustainable.” The Educators Room; and Merrimack College.

48Merrimack College.

49Will, “The Teaching Profession in 2021…”

50Bartlett, Lora. (August 2, 2021) “Will the Pandemic Drive Teachers Out of the Profession? What One Study Says.” Education Week.

51Greenberg; Johnson; Sparks; and Will, “The Teaching Profession in 2021.”

52Lever.

53Johnson.

54Greenberg.

55Bartlett; Greenberg; and Diliberti, M.K., et al., (2021) “Stress Topped the Reasons Why Public School Teachers Quit, Even Before COVID-19,” RAND Corporation.

56Learning Policy Institute, (2017) “What’s the Cost of Teacher Turnover?”

57Berry, B., et al., (2021) “The Importance of Teaching and Learning Conditions: Influences on Teacher Retention and School Performance in North Carolina,” Learning Policy Institute.

58Scholastic Inc.

59Will, “Stress, Burnout, Depression…”

60Causey, A., (2022) “My Drive to Teach: Find Your Why.” Elevating Teachers Blog, Public Education Partners Greenville County.

61Schwartz, S., (2022) “Teacher Morale Is at a Low Point. Here’s Where Some Are Finding Hope.” Education Week.

20250717